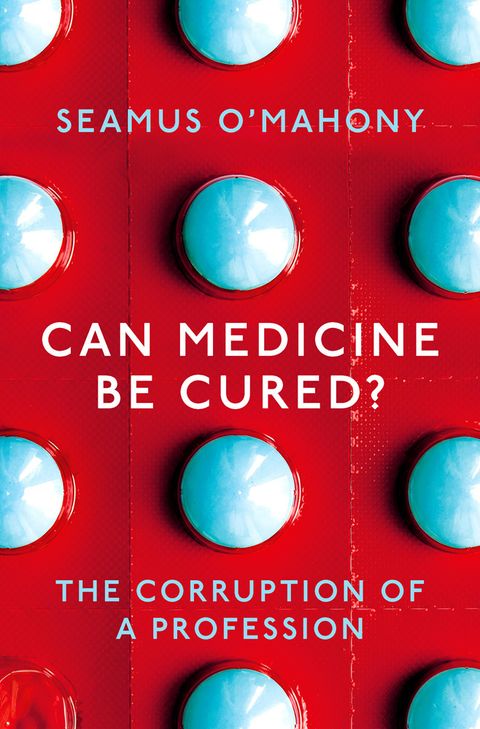

Seamus O’Mahony, a gastroenterologist from Cork, has written the most devastating critique of modern medicine since Ivan Illich in Medical Nemesis in 1975. O’Mahony cites Illich and argues that many of his warnings of the medicalisation of life and death; runaway costs; ever declining value; patients reduced to consumers; growing empires of doctors, other health workers, and researchers; and the industrialisation of healthcare have come true. There is a widespread feeling that medicine has lost its way, and Can Medicine Be Cured? The Corruption of Medicine, which has been published this month, describes the loss. The book is as readable as O’Mahony’s last book The Way We Die Now, and the book provides a strange cocktail of pleasure and despair.

From a golden age to the age of disappointment

Unlike Illich, who believed that modern medicine counterproductively created sickness, O’Mahony does see what he calls a golden age of medicine that began after the Second World War with the appearance of antibiotics, vaccines, a swathe of effective drugs, surgical innovations, better anaesthetics, and universal health coverage for most of those in rich countries. It ended in the late 1970s, meaning that O’Mahony, who graduated in 1983 and is still practising, enjoyed little of the golden age. We are now “in the age of unmet and unrealistic expectations, the age of disappointment.”

Golden ages are always in the past or the future and never now (except perhaps for television), but many older people who remember when people died of polio, diphtheria, and tuberculosis would agree that a golden age did begin around the birth of the NHS in 1948; many older doctors also see that time as a golden age when there was more curing of diseases, patients were mostly grateful and respectful, and doctors had clearer roles and more power and status.

With his liking for religious imagery, O’Mahony describes himself as experiencing apostasy at the age of 50. He has not lost faith in “the clinical encounter, and old-fashioned doctoring” (although still doing an acute take in general medicine, he finds it increasingly exhausting and frustrating), but he has lost faith in “medical research, managerialism, protocols, metrics, and even progress.” The book dissects those realms one by one. Medicine has become “an industrialised culture of excess” and Illich is now right that medicine is a threat to health.

Medical research: good for science, less good for patients

O’Mahony begins his dissection with medical research, “the intellectual motor of the medico-industrial complex.” Governments see life sciences as a saviour of economies, and charities urge us to give more to cure every disease. Big Science, which appeared after the golden age, has provided jobs and status but “benefits to patients have been modest and unspectacular.” A study of 101 basic science discoveries published in major journals and claiming a clinical application found that 20 years later only one had produced clinical benefit. Big Science is corrupted by “perverse incentives, careerism, and commercialisation.” Medical research has become disconnected with medical practice, which when premature mortality has fallen so far is dealing mainly with pain, suffering, and disability. Medical research is still fighting an “unwinnable and unnecessary battle” against death.

Practitioners of genomics promise great benefits for tomorrow (it’s always tomorrow), but the Nobel Laureate and former director of the National Institutes of Health Harold Varmus said that “genomics is a way to do science, not medicine.” Robert Weinberg, a cancer biologist, says that clinical applications from the Human Genome Project “have been modest—very modest compared with the resources invested.”

Macfarlane Burnet, another Nobel laureate wrote, wrote in 1971 that “the contribution of laboratory science [to medicine] has virtually come to an end.” Yet another Nobel laureate Peter Medawar took him to task, predicting in 1980 cures for juvenile diabetes and multiple sclerosis within 10 years. As O’Mahony concludes “history sided with Burnet, not Medawar.” He then makes an amusing, and to some insulting, comparison between contemporary biomedical science and the medieval pre-Reformation papacy: “both were taken over by careerists…[who] saw the trappings of worldly success as more important than the original ideal.” Biomedical research is waiting for its Reformation, perhaps it will come with a shift to much more practical research and an emphasis on making a difference rather than publishing papers.

Inventing and marketing new diseases: the case of “non-coeliac gluten sensitivity”

As a gastroenterologist who has done, as he admits, some lacklustre research on gluten sensitivity, O’Mahony tells the story of “non-coeliac gluten sensitivity” to illustrate the modern medical fashion for inventing diseases, which seems to be easier than curing some of the old ones. Willem-Karel Dicke, a Dutch paediatrician, identified wheat as causing coeliac disease during the wartime winter of starvation in the Netherlands. American paediatric journals didn’t even acknowledge Dicke’s submissions, but eventually gluten was identified as the cause of coeliac disease and some very sick children were cured. Now most adults O’Mahony diagnoses with coeliac disease have minimal or no symptoms.

But as every doctor, and particularly gastroenterologists, know there are many patients with “medically unexplained” or psychosomatic conditions. The stigma attached to mental health problems, reluctance to diagnose what O’Mahony calls “shit-life syndrome,” and the appetite for the medico-industrial complex for inventing diseases means that there is substantial demand for new “physical diseases.” Some patients with gastroenterological symptoms had already experimented with gluten-free diets, and the placebo effect and the fluctuating nature of their symptoms inevitably mean that many would feel better. O’Mahony describes how in February 2011 15 coeliac-disease researchers met in a hotel at Heathrow sponsored by Dr Schar, a leading manufacturer of gluten-free foods, and gave medical credibility to “non-coeliac gluten sensitivity.”

Dozens of scientifically weak scientific papers, review articles, and consensus conferences have followed; and O’Mahony lists from a review article resulting from a consensus conference sponsored by the Nestle Nutrition Foundation 41 symptoms and problems said to result from gluten sensitivity, including tiredness, anxiety, depression, weight loss and gain, disturbed sleep patterns, autism, schizophrenia, and even “ingrown hairs.” “Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity has been decreed by edict,” writes O’Mahony, “just as papal infallibility was decreed by the First Vatican Council.” And the edict means that probably most of the patients seen in general practice each day could be suffering from the condition. Indeed, about 10% of the British population is cutting down on gluten, and the “free-from” food market, 59% of which is gluten-free foods, is huge and growing at 30% a year.

We have arrived, writes O’Mahony, at a “strange paradox: the majority of people who should be on gluten-free diet (those with coeliac disease) aren’t, because most people with coeliac disease remain undiagnosed. The majority of those on a gluten-free diet shouldn’t be, because they do not have coeliac disease.”

With his talent for storytelling and humour, O’Mahony, describes the parallel between current fears of gluten and the “grain-free” monks of China 2000 years ago. They believed that the “five grains” were the “scissors that cut off life,” leading to disease and death. A diet avoiding the five grains would lead to perfect health, immortality, and even the ability to fly.

“Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity” may be one of the most successful non-diseases, but it is by no means alone. Competitors include seronegative Lyme disease, female sexual dysfunction, social phobia, and chronic procrastination syndrome. Inventing and promoting diseases is known as disease-mongering, and a variant of the phenomenon is to lower levels of risk for conditions like hypertension and diabetes, so creating tens of millions more patients overnight.

The marketing of diseases

Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity has been well marketed, but, as far as I know, there is not yet a non-coeliac gluten sensitivity day, week, or month, although there soon may be. O’Mahony was writing his chapter on awareness, or competition between diseases and their followers for resources, in April, which has World Days for autism, health, homeopathy, haemophilia, and malaria. Every disease, like every dog, has its day, but excessive marketing of disease leads to misallocation of resources (“78% of students telling their union that they have mental health problems”), and dubious protocols that distort medical practice.

Twelve year old Rory Staunton died of septicaemia in New York in 2012 after injuring himself playing basketball and his doctors failing to recognise how sick he was. His father, a political lobbyist, set up the Rory Staunton Foundation for Sepsis Prevention, which has led to all state hospitals in New York having to use protocols for screening and treating sepsis and all children in the state having mandatory sepsis education.

Hospitals around the world now have mandatory sepsis protocols, but unfortunately the warning triggers are so vague that they lead to tens of thousands of patients, particularly older ones, being treated unnecessarily with intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and a catheter in their bladders—all of which carry risks. The protocols also lead to “diversion of scarce ICU capacity, and delayed identification of non-sepsis diagnoses.”

Cancer: the number one disease

No disease is better marketed than cancer, and after Richard Nixon’s War on Cancer, Barack Obama launched his Cancer Moonshot, which is now renamed Cancer Breakthroughs under Donald Trump. As O’Mahony writes, the language around cancer “is infected with a sort of hubristic oedema.” For Big Science cancer is a blessing, leading to huge investments in molecular biology and genetics, but, as cancer researcher David Pye put it: “How can we know so much about the causes and progression of disease, yet do so little to prevent death and incapacity.”

In contrast with the paucity of new drugs for brain disorders, many new drug treatments for cancer are appearing—but the gains are tiny and the price astronomic. One review of 14 new drugs found that the average extra life saved was 1.2 months. The treatments often have serious side effects, meaning that the quality of life in those few extra weeks is often poor.

O’Mahony tells the story of A A Gill, the gifted journalist, who had metastatic lung cancer, and was denied by the NHS a new immunotherapy drug nivolumab, which costs £60 000 to £100 000 a year. His oncologist said that if he could he would prescribe the drug “as would every oncologist in the First World.” Gill did get the drug but only shortly before he died. A trial published after Gill’s death showed that treatment with nivolumab added 1.2 months of life to that achieved with standard treatment. O’Mahony calculates that offering the treatment to all those in Britain who might benefit would cost around £1 billion, about the annual cost of hospice care.

“The medical profession,” he writes, “has become the front-of-house sales team for the [drug] industry.” He argues that “doctors’ professional culture obliges them to do something—anything,” but he is too easy on doctors, who could push back. Society, he says, displays “childishness” in going along with these expensive treatments: “we must have higher, and better, priorities than feeble, incremental and attritional extension of survival in patients with incurable cancer.” Cancer is a disease of age, and as the population ages “cancer keeps outrunning us . . . Progress in curing cancer is now reminiscent of the trench warfare of the First World War, where a few hundred yards of territory might be gained at the expense of thousands of lives.”

Oncology is the specialty that is always quoted in these discussions, partly because the data on both benefit and cost are good, but what the economist Alain Enthoven called “flat of the curve healthcare,” where large investments bring small benefits (or even more problems), occurs across medicine. The rising costs are driven primarily by “advances”: “every advance in medical science creates new needs that did not exist until the means of meeting them came into existence.” These advances can also create new and painful problems: should a wife sell the family home in order to get treatment for her dying husband? Should premature babies be kept alive, even though the chances are high that they will be severely disabled, changing instantly the lives of their parents and siblings?

People increasingly know, argues O’Mahony, that health services cannot expand indefinitely “but there is no political or public appetite for . . . [the] difficult conversation” of how to get out of this health arms race.

The decline in the power and influence of doctors

Doctors might have been the ones to lead the difficult conversation, but the power of doctors, argues O’Mahony, has been declining for decades, with much of the decline being their own fault. A series of scandals in the NHS, the appearance of the internet, and the increasing politicisation and monetisation of healthcare have provided the context, and “the medical profession sleepwalked through all of this, ceding leadership to managers and Big Science academics.”

O’Mahony believes that doctors have become “anti-harlots,” with responsibility but no power. He very much has the perception of the acute physician doing the “safari ward round” after a night of multiple admissions, traipsing around the hospital with inadequately trained and overworked junior staff in search of patients, most of them elderly with multiple problems, many of them admitted primarily for social problems—and with politicians promising ever more but insisting on increased productivity and with managers concentrating on targets and finances. Doctors are treating but not healing.

But O’Mahony does not, as do many doctors, blame politicians, managers, journalists, and lawyers for medicine’s woes. “Our complacency and collective cowardice have placed us where we are now . . . Doctors are so divided by factional fighting and ‘boosterism’ for our diseases and services that we no longer function as a cohesive profession pursuing a common good. We have poisoned the well of our craft and tradition.”

Can medicine be cured?

O’Mahony’s book is titled Can Medicine Be Cured? He doesn’t give a yes or no answer, but he is pessimistic about the profession’s capacity for reform. “Leadership” has become the standard solution to reform of medicine and healthcare, and he goes along with the idea—but says the leadership must not be “limp-wristed virtue signalling,” and he cannot see where it will come from. “Too many have a vested interest in unreformed medicine continuing.”

Crisis drives reform, and O’Mahony thinks that some combination of economic collapse, a global pandemic of an untreatable infection, and climate catastrophe will force medicine back to “providing basic measures such as immunisation, trauma care, and obstetrics.”

The first thing that I ever had published in a medical journal was a letter to the Lancet in 1974 asking why there had been no response to an article in the journal by Ivan Illich describing in detail how modern medicine was a threat to health. (It would cost me $35.95 today to access the letter, about 50 cents a word from memory.) As a medical student I expected that the leaders of medicine would carefully dissect Illich’s argument and with evidence show him to be wrong. But such a response never came. I was naive: I know now that it’s easier simply to ignore cogent criticisms. I hope that O’Mahony’s book, a Medical Nemesis for 2019, will not be ignored. It deserves to be taken very seriously.

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.