When our immune systems mobilise, they can sometimes go into overdrive, triggering a destructive over-reaction called a cytokine storm. Why does it happen, and how can we stop it?

As Covid-19 cases fill the world’s hospitals, among the sickest and most likely to die are those whose bodies react in a signature, catastrophic way. Immune cells flood into the lungs and attack them, when they should be protecting them. Blood vessels leak, and the blood itself clots. Blood pressure plummets and organs start to fail.

Such cases, doctors and scientists increasingly believe, are due to an immune reaction gone overboard – so that it harms instead of helps.

Normally, when the human body encounters a germ, the immune system attacks the invader and then stands down. But sometimes, that orderly army of cells wielding molecular weapons gets out of control, morphing from obedient soldiers into an unruly, torch and pitchfork-bearing mob. Though there are tests and treatments that could help to identify and tamp down this insurrection, it’s too early to be sure of the best course of therapy for those who are suffering a storm due to Covid-19.

Variants on this hyperactive immune reaction occur in an array of conditions, triggered by infection, faulty genes or autoimmune disorders in which the body thinks its own tissues are invaders. All fall under the umbrella term “cytokibe storm”, named because substances called cytokines rampage through the bloodstream. These small proteins — there are dozens – are the immune army’s messengers, transiting between cells with a variety of effects. Some ask for more immune activity; some request less.

Here’s what scientists know about cytokine storms and the part they play in Covid-19.

Rising storm

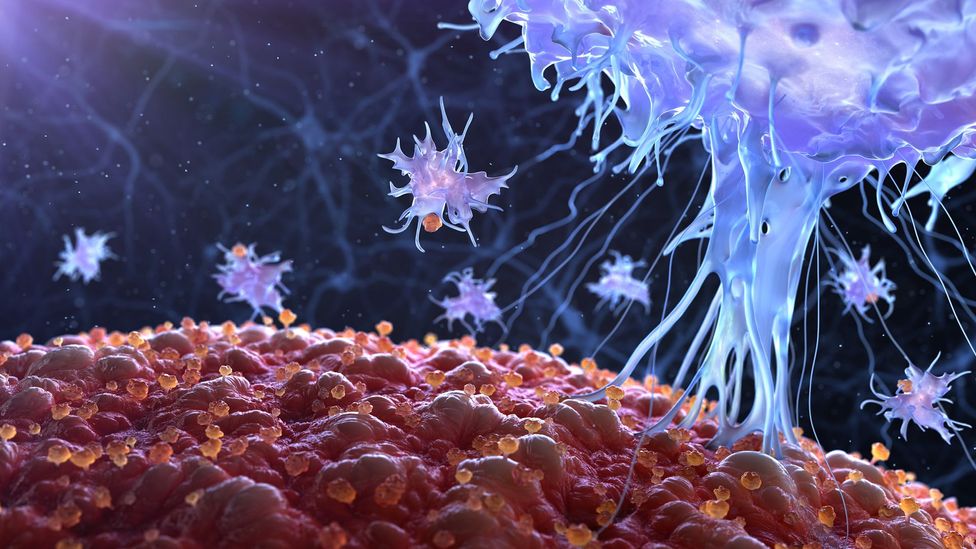

When the cytokines that raise immune activity become too abundant, the immune system may not be able to stop itself. Immune cells spread beyond infected body parts and start attacking healthy tissues, gobbling up red and white blood cells and damaging the liver. Blood vessel walls open up to let immune cells into surrounding tissues, but the vessels get so leaky that the lungs may fill with fluid, and blood pressure drops. Blood clots form throughout the body, further choking the blood flow. When organs don’t get enough blood, a person can go into shock, risking permanent organ damage or death.

Most patients experiencing a storm will have a fever, and about half will have some nervous system symptoms, such as headaches, seizures or even a coma, says Randy Cron, a paediatric rheumatologist and immunologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and co-editor of the 2019 textbook Cytokine Storm Syndrome. “They tend to be sicker than you expect,” he says.

Doctors are only now coming to understand cytokine storms and how to treat them, he adds. Though there’s no failsafe diagnostic test, there are signs that a storm may be underway. For example, blood levels of the protein ferritin may rise, as may blood concentrations of the inflammation indicator C-reactive protein, which is made by the liver.

The first hints that severe Covid-19 cases included a cytokine storm came out of Chinese hospitals near the outbreak’s epicentre. Physicians in Wuhan, in a study of 29 patients, reported that higher levels of the cytokines IL-2R and IL-6 were found in more severe Covid-19 infections.