KOLESTEROL İLAÇLARININ YAN ETKİSİ FAYDASINDAN DAHA ÇOK

Dikkat: Yazının sonunda ek var!

***

Daily Mail gazetesinin haberi:

International Society for Vascular Surgery Başkanı Professor Sherif Sultan diyor ki:

BİR: Kolesterol hapları (statinler) hiçbir hastada ölüm oranlarını azaltmaz.

İKİ: Statin kullanımını destekleyen bütün araştırmalar peşin hükümlüdür.

ÜÇ: Statinler kalp krizleri için risk faktörü olan damar sertliğini hızlandırır.

DÖRT: Statinler diyabet, meme kanseri, sinir hasarı ve hatta katarakt riskini artırır.

BEŞ: Statinlerin çocuklarda ve 62 yaş üzerinde faydalı olduğunun bir delili yoktur.

Prof. Sultan şöyle devam ediyor:

Statinlerin yan etkileri herhangi muhtemele faydalarından daha fazladır.

Bir hastalığı önlemek için bu ilaçları alanlar aslında bir felaket yaratıyorlar.

Bu ilaçlar, her 100 kişiden birinde görme bozukluları ve kanama, 100 kişiden birinde karaciğer ve pankreas enflamasyonu, 10 kişiden birinde baş ve kas ağrılarına sebep oluyor.

Statinler Birleşik Krallık’ ta her dört erişkinden birine yazılıyor.

Sultan’a göre statinler istatistik hileleriyle faydalı gibi gösteriliyor.

Geçmişte yapılan çalışmaların statin üreticileri tarafından çalıştırılan bilim adamlarının peşin hükümlerinden etkilenebileceğini vurguluyor.

Bazı çalışmalar tam aksine kalp krizleri için risk faktörü olan damar sertliğini hızlandırabilir.

Statin kullanımı ile diyabet, katarakt, iktidarsızlık, meme kanseri, sinir hasarı, depresyon, kas ağrısı, böbrek ve karaciğer yetersizliği arasında bir bağlantı vardır.

Sultan, bu ilaçların çocuklara ve 62 yaş üzerinde olanlara bu gruptakilerde faydasını gösteren hiçbir delil olmadığı için kesinlikle yazılmaması gerektiğini ilave ediyor.

Yan etkiler gizleniyor

Royal College of Physicians eski Başkanı Sir Richard Thompson da Sultan ile aynı görüşleri paylaşıyor:

“Bu ilaçların özellikle yan etkilerini gizlenmiş olmasından endişe duyuyoruz.”

Statinler etkili ilaçlardır

Buna karşılık bu ilaçları doktor tavsiyelerine rağmen kesenlerin hayatlarını riske attıklarını ileri sürenler de var.

Medicines Healthcare Regulatory Agency’ den Dr June Raine “Statinlerin faydaları çok iyi belirlenmiştir ve hastaların çoğunda yan etkilerinin riskinden çok daha fazladır” diyor:

Statinlerin etkinliği ve emniyeti çok sayıda büyük araştırmada araştırılmış ve bunların kolesterolü azaltarak kalp-damar hastalıklarını azalttıkları ve hayatlarını kurtardıkları gösterilmiştir.

Bunların ciddi yan etkileri son derecede enderdir.

British Heart Foundation’ a göre tehlikeli yan etkiler statin alan 10 bin hastanın sadece birinde görülür.

Kaynak: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-4439808/The-effects-statins-outweigh-benefits.html

***

EK 1 (15.9.2022): MARYANNE DEMASİ Do statins cause muscle aches?

Cholesterol-lowering medications called statins are widely prescribed, however, about 50% of patients dump their statins within a year of commencing therapy.

The most common complaint is muscle problems – pain, weakness, cramps, and aches.

But now, a major study published in The Lancet has concluded that statins are rarely to blame.

The study has garnered international media attention and left many patients wondering if their doctors will believe them if they complain about muscle pains after taking a statin.

The following analysis argues that the conclusion of this new study is misguided and highlights how the design of industry-funded statin trials has led to the obfuscation of muscle harms.

Who did the study?

The study was conducted by researchers from the University of Oxford’s Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration.

The group famously entered into a legally binding agreement with the industry sponsors of the statin trials to allow it exclusive access to the ‘individual participant data.’

There was one condition though. The group could not share the trial data with third party researchers, thereby preventing independent scrutiny.

This has been a sore point for many independent researchers who say, science, by its very nature, requires contestability.

The CTT group sits under the umbrella of the Clinical Trial Service Unit (CTSU) at Oxford, an organisation that has received over £260million in research funding from the drug industry, the vast majority from manufacturers of cholesterol-lowering drugs.

The findings

The CTT’s meta-analysis of 23 randomised clinical trials involving 155,000 individuals, found that statins were not the cause of muscle pain in over 90% of those who experienced symptoms, and likely due to “other conditions” such as ageing.

In 19 trials of statin therapy versus placebo, there was less than a 1% difference in the number of people who reported symptoms (27.1% statins vs 26.6% placebo).

The rates of muscle harms remained consistent across different brands of statins and under different clinical circumstances, although higher doses were associated with a sightly higher risk.

The CTT group concluded that muscle symptoms are common in the population, and that any small increase observed with statins doesn’t outweigh the cardiovascular benefits.

Expert analysis

1. If you don’t look, you won’t find

A valid assessment of muscle harms will ultimately depend on whether the original trials were able to ascertain reliable rates of muscle pain in the placebo and statin arms of the trial.

Peter Doshi, Associate Professor at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy said, “If the answer is ‘no’, then crunching the trial numbers together doesn’t really help us as we could be in a garbage-in, garbage-out situation.”

Doshi went on to say, “If a trial does not properly survey patients for a specific type of adverse event, the reported rates of those events may be completely unreliable. In other words, inadequate data collection can render the results ambiguous or meaningless.”

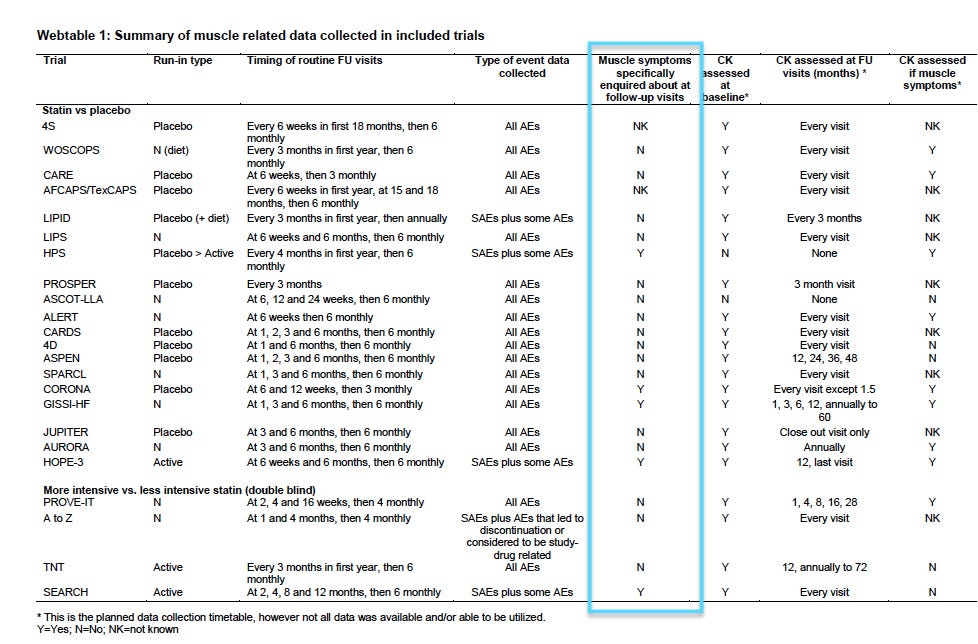

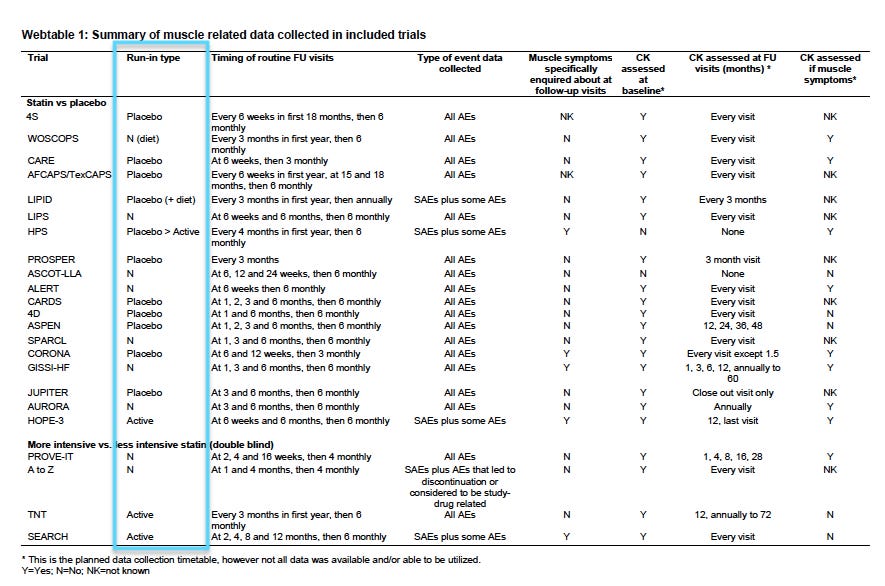

In the CTT analysis, the majority of statin trials – 78% (18/23) – either did not specifically enquire about muscle harms, or it remained unknown. (See Webtable 1).

Therefore, without active solicitation of muscle-related adverse events, a reliance on this type of passive surveillance system means that harms could occur without being documented.

Notably, there was no consistency in the way muscle harms were documented between statin trials and no defined criteria for labelling muscle harms, so aggregating the data in a meaningful way, was problematic.

The CTT authors acknowledged the limitation of their study:

The aggregate rate of reporting of any muscle pain or weakness (ie, for statin and placebo groups combined) during the first year of treatment varied substantially by trial (appendix p 10), from 1·0% to 60·5%, reflecting heterogeneity in how actively information was sought.

“That’s pretty extreme heterogeneity,” said Doshi.

The finding, however, was unsurprising to him. Doshi’s research team obtained statin trial data from Canada’s drug regulator to analyse the methods used to ascertain muscle-related events – their analysis of 23 trials was published recently in the J Gen Intern Med.

“Only 1 trial had such a dedicated surveillance and reporting system. Of the remaining 22 of 23 trials, we found they lacked adequate data collection methods to ascertain rates of muscle related adverse events,” said Doshi.

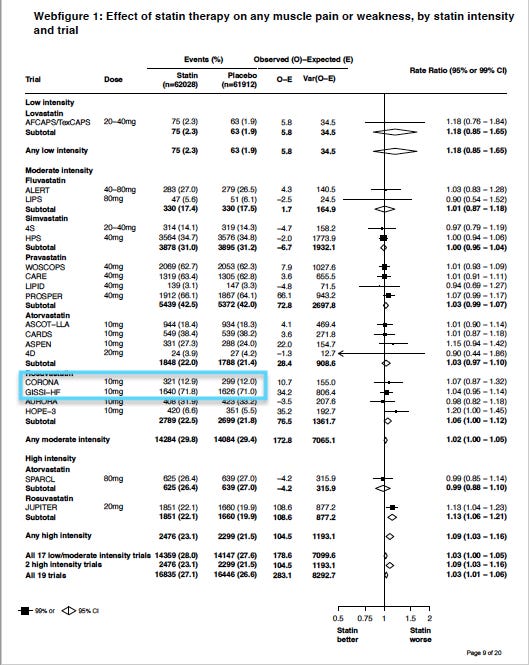

He pointed me to 2 major statin trials – CORONA and GISSI-HF. Both trials were designed similarly and recruited similar cohorts, i.e. patients with heart failure, but the placebo groups were strikingly different.

In the CORONA trial, the placebo group reported 12% muscle harms, compared to 71% in the GISSI-HF trial. (see Webfigure1)

Doshi said, “The wildly different rates in what seem like similar patient populations suggests that the determination of whether somebody has muscle symptoms is highly dependent on how the questions are asked by the trial investigator. That is rather problematic.”

2. Excluding trial participants

The exclusion criteria used in many statin trials has been the subject of intense criticism.

Beatrice Golomb, Professor at the University of California San Diego has questioned why the CTT analysis only included studies with a treatment duration of 2 years or more, excluding those with a shorter duration.

“What could have been the justification for this when they know that muscle pain is an outcome that usually emerges within the first couple of months after initiating a statin?” said Golomb, who has spent decades researching the impact of statins on muscles.

Golomb added, “What this ensures, is that only the largest trials, which are most likely to be industry-funded, are included in the analysis and smaller publicly-funded trials, are not.”

Golomb explained that it was possible to set criteria for selecting or excluding trials in a meta-analysis that would favour the benefits of the statin and underplay the harms.

She was highly critical of the CTT analysis because it included trials that used active “run-ins,” something she considered a design flaw in a trial, especially when analysing harms.

An active ‘run-in’ means that all potential subjects are given the active drug for several weeks and at the end of that period, anyone who was non-compliant or did not tolerate the drug, is excluded from the trial prior to randomisation.

“Effectively, you’ve selected out the people who will not comply with the drug, or who drop out because they experience muscle pain, so then muscle problems in the trial may be seriously under-reported,” said Golomb.

In the Heart Protection Study, for example, they removed 36% of participants from the trial once the run-in period was complete, and only those who remained were randomised to placebo or a statin.

“It’s brazen to do that and it’s so obviously distorting,” said Golomb.

Four trials in the CTT analysis used ‘active drug’ run-ins, while 10 trials used ‘placebo pills’ for the run-in period. (see Webtable 1)

Another way of obscuring muscle harms in statin trials, is to exclude participants who have a history of statin intolerance or those who have raised creatine kinase (CK) levels, an enzyme that indicates muscle damage when elevated.

In the CTT analysis of 23 trials:

-

2 trials excluded subjects with ‘statin intolerance’ (ASCOT-LLA, PROVE-IT),

-

4 trials excluded anyone with a known history of statin-induced myopathy (4D, CORONA, AURORA, JUPITER),

-

1 trial excluded people with known ‘contraindication to statins’ (HOPE-3), and

-

1 trial excluded anyone with a history of non-traumatic rhabdomyolysis (A-Z trial)

Further, 15 statin trials in the analysis excluded patients with elevated CK levels (mainly, CK levels >3x the upper limit of normal).

Obviously, the CTT analysis, which contained a significant proportion of trials that excluded participants who had experienced, or might’ve experienced, muscle problems would generate results that are not generalisable to the broader population.

Why is this important?

While muscle pain is not immediately life threatening to most people, it can adversely impact a person’s quality of life and limit mobility, particularly in the frail and elderly. Physical activity is a central preventive measure for heart disease, as well as many other diseases.

Typically, muscle problems reported in clinical trials have been described as ‘rare’ (<5%), but most clinicians I spoke with, even those who regularly prescribe statins, report the rate is closer to 20%.

Weighing up the benefits and harms of statins becomes critical when you consider that the majority of people prescribed statins are at low risk of heart disease (primary prevention).

“With trials, the devil is often in the detail — for example, I have no idea how data were collected from those who discontinued treatment because of side effects — and so ultimately I am left with questions, and I don’t feel we’ve gotten to the bottom of this issue of statin associated muscle symptoms,” said Doshi.

The implication of this new study is that patients who experience muscle harms after taking a statin are experiencing the ‘nocebo’ effect – i.e. the mere ‘suggestion’ that statins might induce muscle pain is making people imagine they have muscle pain, and negative media coverage is often blamed for that influence.

However, many patients who discontinue their statins notice that their symptoms resolve, and only return once they resume their medication.

“The experiences of patients who develop these symptoms on resuming a statin (rechallenge) must be kept in mind because a rechallenge is also a hallmark feature of causality determination,” said Doshi.

***

Peki sonuç?